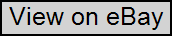

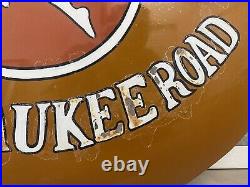

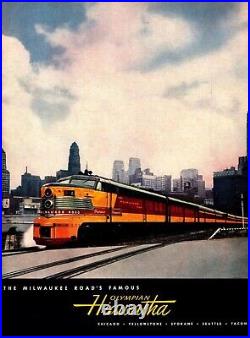

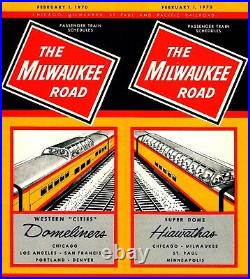

This is a seldomly seen and RARE Vintage Old Olympian HIAWATHA Milwaukee Railroad Painted Sign, hand-painted, advertising the Olympian Hiawatha Milwaukee Road line. This train system was introduced in 1947, and sadly only lasted until 1961, when the Milwaukee Road bowed out to the Pacific Northwest market. This sign is painted in the striking orange colors that became synonymous with the brand and reads: “Olympian Hiawatha – The Milwaukee Road” along the edges. In the center is the stylized Art Deco profile portrait of a Native American chief, which was the classic emblem of the Hiawatha train company. Approximately 27 1/4 inches tall x 28 inches wide, and 1 1/2 inches deep. I have done some extensive research and could not find any sign comparable to this one, and I believe it is quite rare. Good overall condition for decades of age and outdoor display use, with some mild oxidation, paint loss, light denting and scuffs throughout please see photos carefully. Due to the large size of this piece, S&H costs will be unavoidably high. Acquired from an old collection in Pasadena, California. If you like what you see, I encourage you to make an Offer. Please check out my other listings for more wonderful and unique artworks! In the late 1940s the Milwaukee Road introduced the. The transcontinental version of the railroad’s very popular fleet of. The original version of the train was the. Which began operating between Chicago and the Twin Cities on May 29, 1935, one of the first streamlined trains ever to be introduced in the U. For the Milwaukee Road, the Hiawathas were virtually the only streamlined passenger trains run by the railroad (they certainly were the most popular and well-remembered) with the rest operated in conjunction with Union Pacific. Originally powered by 4-4-2 Atlantic-type steam locomotives (later 4-6-4 Hudson-types) the train was entirely streamlined, including the locomotive, and home-built in the Milwaukee’s own shops. These trains became instantly successful and regularly cruised over 100 mph with nary a bump or shudder during the ride (both trains could make the jaunt between the two cities in roughly six hours). These regional trains offered by the Milwaukee Road became so successful that the railroad found itself short on demand and to meet such eventually operated two versions of the train, the. There were eventually four versions of Milwaukee Roads’ regional. (Served New Lisbon, Wisconsin to Minocqua, Wisconsin). (Served Chicago; Ontonagon, Michigan; and Milwaukee and Green Bay). (from Chicago this train served both Omaha, Nebraska and Sioux Falls, South Dakota). With the success of its regional. In 1947, about twelve years after the railroad first launched its. The railroad introduced the streamlined. A train meant to fully compete with the Great Northern and Northern Pacific for rail travel to and from the Pacific Northwest. The Milwaukee had operated the. Since 1911 over its Pacific Extension but these trains used heavyweight equipment and were pulled by conventional steam locomotives. The Milwaukee Road’s. Owe their creation to industrial designer Otto Kuhler, the same man who designed the Baltimore & Ohio’s regal. And its classic royal blue, gold, and gray livery. Kuhler designed similar stunning features on the. However, it was Brook Stevens, who designed the celebrated Sky Top sleeper-lounge observations (perhaps the most distinctive and dramatic observation cars ever built) that created the Milwaukee Road’s Olympian Hiawatha. When the train initially began on June 29, 1947 it included a mix of heavy and lightweight cars but by 1949 when the Pullman equipment arrived it was an entirely streamlined, lightweight train. For power the train featured Erie-Built, diesel locomotives manufactured by Fairbanks-Morse. These locomotives were originally designated to handle the train between Minneapolis and Tacoma, even in electrified territory, according to Jim Scribbins’ book. The Milwaukee Road Remembered. However, they were eventually replaced with electrics between Harlowton, Montana and Avery, Idaho and then again between Othello, Washington and Seattle. While aesthetically quite stunning with added touches by Brooks Stevens of a chromed-nose design with “Olympian Hiawatha” adorning the locomotive along its forward flanks, the Erie-Builts were not very reliable, which led to their replacement. Sadly, the train lasted a mere 14 years and the Milwaukee Road bowed out of the Pacific Northwest market, canceling the train in May of 1961. Interestingly, while the railroad claimed lack of ridership on the. Also of interest is how well each of the three lines actually fared from an operating standpoint. According to railroad historian and civil engineer Michael Sol, the ICC’s official statistics from 1959 contain the following operating ratios for passenger service. Milwaukee Road = 148.7%. Great Northern = 177.4%. Northern Pacific = 194.3%. Perhaps of greater note here is that, in actuality, the three railroads did not really “compete” with their transcontinental services as all served different intermediate points between Seattle and Minneapolis/Chicago. Additionally, by the time the. Was launched there were increasingly fewer passengers riding these trains the entire way (Seattle – Minneapolis/Chicago); most boarded or de-boarded somewhere in between. From a railfan’s and historian’s (and even a traveler of the time period) perspective it’s a shame that the. Was canceled so early considering it operated through some of the most stunningly beautiful areas of the country. In any event, today, while Amtrak carriers on the legendary Hiawatha service, to some degree, offering. Regional trains between Milwaukee and Chicago, the. And the route it traveled are sadly relegated to history and the memories of those who were lucky enough to ride it. In the 1970s the Milwaukee Road began making dumbfounding managerial decisions that ultimately led to the railroad’s undoing in the late 1970s and subsequent abandonment of all lines west of Terry, Montana. The fabulous OLYMPIAN HIAWATHA Streamliner. In the late 1940s, the Milwaukee Road introduced the Olympian Hiawatha, the transcontinental version of the railroad’s very modern fleet of Hiawatha passenger trains. The original version of the train was the Twin Cities Hiawatha, which began operating between Chicago and the Twin Cities on May 29, 1935, one of the first streamlined trains ever to be introduced in the U. For the Milwaukee itself, the Hiawathas were virtually the only streamlined passenger trains run by the railroad (they certainly were the most popular and well-remembered) with the rest operated in conjunction with Union Pacific. Powered initially by 4-4-2 Atlantic-type steam locomotives (later 4-6-4 Hudson-types) the train was entirely streamlined, including the locomotive, and home-built in the Milwaukee’s own shops. These regional trains offered by the Milwaukee Road became so successful that the railroad found itself short on demand and to meet such eventually operated two versions of the train, the Morning Hiawatha, and the Afternoon Hiawatha. There were eventually four versions of Milwaukee Roads’ regional Hiawathas. They included the Twin Cities Hiawatha, North Woods Hiawatha (served New Lisbon, Wisconsin to Minocqua, Wisconsin), Chippewa Hiawatha (served Chicago; Ontonagon, Michigan; and Milwaukee and Green Bay), and the Midwest Hiawatha (from Chicago this train served both Omaha, Nebraska and Sioux Falls, South Dakota). However, these Midwest versions were not the only Hiawathas the Milwaukee ever operated. With the success of its regional Hiawathas, in 1947, about twelve years after the railroad first launched its Hiawatha the railroad introduced the streamlined Olympian Hiawatha, a train meant to fully compete with the Great Northern and Northern Pacific for rail travel to and from the Pacific Northwest (the Milwaukee had operated the Olympian and Columbian since 1911 over its Pacific Extension but these trains used heavyweight equipment and were pulled by conventional steam locomotives). The Milwaukee Road’s Hiawathas owe their creation to industrial designer Otto Kuhler, the same man who designed the Baltimore & Ohio’s regal Capitol Limited and its classic royal blue, gold, and gray livery. Kuhler designed similar stunning features on the Hiawathas. Sadly, the train lasted a mere 14 years, and the Milwaukee Road bowed out of the Pacific Northwest market, canceling the train in May of 1961. From these numbers, it is clear to see that despite what you may have previously read or understood about Milwaukee’s Northwest flagship, the railroad was far more efficient than its competitors with transcontinental rail service. However, that’s not to say that it was a “better” train, simply that it was operated more efficiently (in truth, all three railroads fielded magnificent trains to Seattle). Of greater note is that in actuality the three railroads did not really “compete” in the truest sense of the word as, except for the Northern Pacific, all served different intermediate points between Seattle and Minneapolis/Chicago. Additionally, by the time the Olympian Hi was launched there were fewer and fewer passengers riding such trains from end-point to end-point (Seattle to Minneapolis/Chicago) as most boarded or de-boarded somewhere in between. From a railfan’s and historian’s (and even a traveler of the time period) perspective it’s a shame that the Olympian Hi was canceled so early considering it operated through some of the most stunningly beautiful areas of the country had to call it quits barely into the 1960s. In any event, today, while Amtrak carriers on the legendary Hiawatha service, to some degree, offering Hiawatha regional trains between Milwaukee and Chicago, the Olympian Hiawatha and the route it traveled are sadly relegated to history and the memories of those who were lucky enough to ride it. Paul and Pacific Railroad. The Olympian Hiawatha took scheduled excursions through scenic Idaho, Montanas Bitterroot Mountains, and Washingtons Cascade range. On June 29, 1947, the Milwaukee Road inaugurated its streamlined flagship on a 43-hour, 30-minute schedule. This was advertised as being a speedliner. The railroad contracted industrial designer Brooks Stevens to design the train consist, which included some unique and signature cars of the Milwaukee Road. In 1952, the first full-length Super Dome cars were added, which included 68 dome seats and 28 lounge seats. The dome area featured seats positioned lengthwise, facing the 625 square foot double-pane windows. Ideal for insulation, and sightseeing. In 1955, the Milwaukee Road announced that they would operate Union Pacific streamliners between Chicago and Omaha. This meant that the Hiawatha would be painted in Union Pacific’s Armour Yellow colors. In 1956, the line was officially “partnered with Union Pacific” as they navigated the next couple years competing with both airline and automobile travel. The Hiawatha train wore the UP colors into the sunset as The Afternoon Hiawatha ran up until January 23, 1970. The next year, The Morning Hiawatha service was also discontinued and replaced by Amtrak lines. In the late 1800’s the Milwaukee Road was a prosperous railroad out of Chicago that had over 6,000 miles of track in the upper Midwest. Experiencing competition from other rail lines, the company decided to expand west to take advantage of the expanding West Coast markets, as well as the Pacific Rim trade. The route proposed for the new line was through the rugged Bitterroot Mountains. Prior to preparing official plans for the construction, significant exploration had to be undertaken to select the most feasible route. Various possibilities existed westward of Butte and up beyond Missoula. The exploration and reconnaissance crews reportedly covered over 2,000 miles crossing the territory of many Tribal nations along the way in country that was wild, with very few trails, and virtually no maps. The exploration work on the Montana side began in November, 1904. The exploration on the Idaho side began in May, 1905. In November of 1905, the Milwaukee Railroad Board of Directors formally approved the lines extension to Seattle-Tacoma, Washington. Because time was an enormous factor, the crews worked year round and did not stop because of winter weather. By the spring of 1906 the choices were narrowing to the St. Paul Pass and St. After the exploration surveys, during most of 1906 engineering survey crews finally helped select and identify the actual location of where the tracks would be located. By early in 1907 the construction work began. The actual construction of the rail bed and the track was very difficult due to the forbidding terrain and the weather conditions. All in all it took nearly 9,000 men, Italians, Serbs, Montenegrins, Austrians, Belgians, Hungarians, Japanese, French, Canadians, Spaniards, Irishmen, Swedes, Norwegians, and others all working together from 1906 to 1911 to construct this Pacific extension. As the construction proceeded, numerous settlements sprouted throughout the area. Avery was the division point on the line and became one of the more substantial settlements. Others were just very rough construction camps, with evenings full of riotous gambling, drinking, dancing, and fighting. In August of 1910 one of the most devastating forest fires in recorded American history burned much of the natural forests in Northern Idaho and Western Montana. The fire burned 2½ to 3 million acres. It was so huge that a massive cloud of smoke spread throughout Southern Canada and the Northern United States all the way to the St. The darkness from this smoke was so bad that for 5 days artificial lighting had to be used from Butte, Montana including Chicago to Watertown, New York. The fire completely devastated the St. Joe River valley and destroyed all of the towns except Avery and Marble Creek. Many of these were never rebuilt. There were numerous stories of very heroic actions by the railroad employees who drove engines and box cars filled with people through the flames to the safety of the longer tunnels. Reportedly over 600 lives were saved in this manner alone. After this disastrous fire, as well as for some other operating reasons, the Milwaukee Road made the decision to electrify the. Line (use electric locomotives) between Avery and Harlowton. Montana, a distance of 440 miles. This innovation by the railroad was the first use of electrification over an extended distance and was watched over very closely by other railroaders. The results were astounding both in terms of reliability of operations as well as profitability. These were the glory days of the railroad, which was then called the Chicago, Milwaukee and Puget Sound later to be the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Still, despite its accomplishments, the railroad had more than its share of hardships, it was forced into. It was reorganized 18 months later. In the years between 1921 and 1940 it only had three years in the black. The railroad declared another bankruptcy in 1935. The advent of the speedy 100 m. But even that was short-lived, and gradually through various reductions of services this once proud railroad gradually deteriorated. The last passenger train, the Olympian Hiawatha passed through the Bitterroots in 1961, and the electric locomotives where gradually replaced by diesel engines by 1973. The final bankruptcy was filed in 1977, and the last train west of Butte passed through in 1980. After that the line was abandoned. While the Chicago-Seattle-Tacoma, Washington. Was around long before the original. Hit the rails, it wasn’t until June 29, 1947, when it too received the Hiawatha treatment. In competition with the Great Northern’s. And Northern Pacific’s. Aimed to break the mold with industrialist designer, Brooks Stevens as an ally. The postwar streamliner introduced quality passenger and sleeper accommodations from Pullman-Standards with designs of larger dimensions than the original Hiawatha cars. This was followed by Steven’s unique Skytop Lounge bedroom-observation cars. Super Dome, the very first full-length dome car on the Milwaukee Road, provided a 360-degree panoramic view when introduced on the train in 1952. From 1947 to 1961, the. Traversed the railroad’s Pacific Extension through the Rocky and Cascade mountains. The full-length dome car, known as the Super Dome, is another distinguishing characteristic of later Hiawathas. The Milwaukee Road issued this timetable with the inauguration of its new “speedlined”. On June 29, 1947. To compete with Great Northern, which had introduced its fully streamlined. Four months before, the Milwaukee hastily put the. Into service before Pullman had been able to deliver streamlined sleeping cars, including the famous Sky Top observation cars. For first-class passengers, the train used heavyweight sleepers until early 1949. The timetable also reintroduces the. Which had been cancelled in the early part of the Depression. The revived train used equipment from the. And operated on the. S former schedule, which took about 12 hours longer than the. S 45-hour Chicago-Seattle schedule. Included a diner, a Tip-Top Grill car, one heavyweight sleeping car with six sections and six double bedrooms; a heavyweight observation-lounge-sleeping car with three compartments and two drawing rooms; three streamlined coaches; two streamlined Touralux sleeping cars; and finally an unusual streamlined car that was half Touralux with eight sections and half coach with 20 seats. This car was designated for women and children only. Passengers in the Touralux cars wouldn’t have access to the observation car, which would have left the observation lounge pretty empty with a maximum of 36 passengers to support it. In contrast, the 1947. Had two full sleeping cars plus an observation-lounge-sleeper; only one tourist sleeper; and three coaches. The train offered a full diner but did not have a grill car like the Tip-Top car, which would have been welcomed by coach passengers. While coach and tourist sleeper passengers were allowed to use the diners, the prices in grill cars were substantially lower due to the use of paper instead of cloth table cloths and napkins and similar economies. After the lightweight sleepers were delivered in 1949, the. Carried as many as four coaches, three Touralux cars, three first-class sleepers, and the Sky Top car which included eight bedrooms, plus of course a diner and grill car. This timetable also shows schedules for several other trains, including the. Between Chicago and Minneapolis. S westbound schedule is shown without an identifying name, but the eastbound schedule is missing entirely. The schedules also show milk-run trains between Minneapolis and Marmarth, ND which had the same numbers as the. Even though it didn’t connect with that train in Minneapolis; Miles City and Harlowton, Montana (a three-days-a-week mixed train); and between Butte and Spokane. These local trains would soon disappear from the timetables.